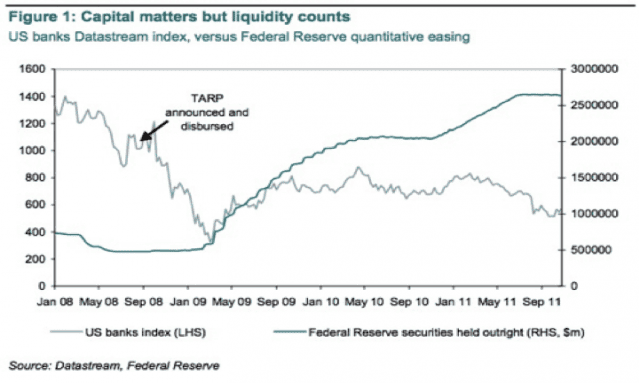

All eyes are trained on Europe these days. While I look on, I can’t help but yearn for the day when financial markets and financial institutions are a little less interconnected, and a lot more resilient. Whether such a system lies in the future, or only in the past, is open to question. It’s clear that the factious nature of the nation state, the shape of the financial system, the depth of debt in which the nations are locked, and the seriousness of the ecological crisis we all face make the project of global economic interdependence difficult. Europe needs to do three things if the dream of a single European currency is to be salvaged and wide-spread depression is to be avoided. First, although near-term austerity will only make matters worse, long-run fiscal discipline must be restored country-by-country. While the agreement this week is no doubt a step in the right direction, it’s hard to hold out much hope that this time really will be different. The deficits hampering many European countries are as much the direct result of the bank-induced financial collapse, and structural demographic and cultural challenges, as they are the consequence of government fiscal irresponsibility. It is hard to imagine true centralized fiscal control when national interests are at conflict with the perceived European objectives dictated by a powerful minority, perhaps a minority of one. It is conceivable, and in my judgment likely, that this is one of the many fatal flaws of the project. Countries will regret giving up the resilience provided by sovereign currencies and central banks that can control domestic monetary policy. Even if we assume for a moment there is a “fiscal fix,” there needs to be a credible recovery plan beyond near-term austerity. Second, a healthy banking sector is a prerequisite for a sustainable economic union. European banks are dangerously undercapitalized with large, unrealized losses weakening their real capital positions as the market well understands. In a vote of no confidence, the stock market values large banks at less than half their book value. Large European banks run reckless liquidity mismatches, with American money market funds funding their speculation in long-dated and now illiquid European sovereign bonds. What value is that adding to the real economy anyway? Regulators should force the banks to raise equity, diluting current shareholders as they rightly should, rather than allow the banks to simply dump assets into the already weak credit markets. If the banks fail to raise the equity, regulators should declare them insolvent, nationalize them, replace management, and sell off the parts. This will allow capital to form around new banking enterprises that are appropriately scaled and have the boring utility-like business models we need, focused on domestic and regional recovery (rather than Jon Corzine style financial speculation). Third, if the US experience is any guide, the European Central Bank will need to amend its charter and get busy pumping liquidity into the system. As the chart below nicely illustrates, capital is important but liquidity is what saved the system. My apologies to the source, I simply cannot find where it came from.

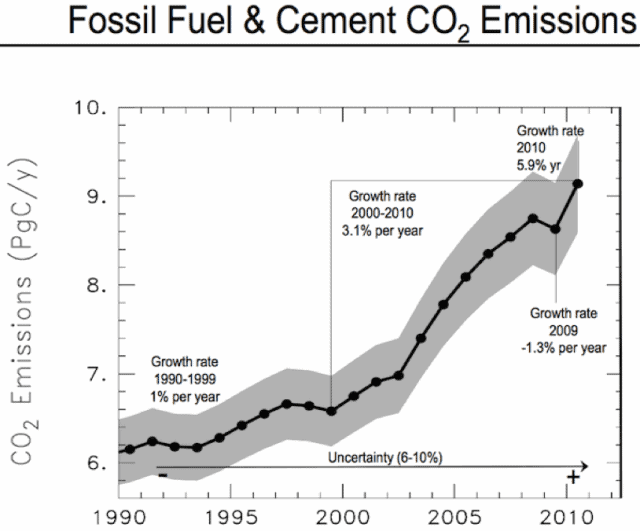

This of course leaves the risk of future inflation, but at least the two dominant currency blocks would remain more in sync. It is worth noting how treacherous the times we live in are when the smartest economists in the world cannot agree on whether the greatest near-term threat is inflation or deflation. A viable alternative exists to flooding the markets with liquidity and supporting sovereign debt prices to save the banks, namely, a debt jubilee of some sort, like the one being negotiated with Greece. Doing this quickly would require a banking system recapitalization that is truly hard to fathom. A lot of those US money market funds that have invested in French bank commercial paper would receive devalued bank stock in return. But history and corporate experience show that without a realistic “balance sheet restructuring,” the boot of excessive debt on the necks of society will preclude economic recovery. At the same time, risks of social unrest continue to grow due to the unfair hardship imposed on ordinary citizens for the mistakes and frauds – see Italian and Greek debt-hiding financing schemes with JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs — of their governments, and the irresponsibility of their bankers. Social unrest can quickly explode debt to GDP ratios far faster than austerity can fix them. One additional cloud lingers on the horizon, ironically discussed in Durban, South Africa, at the COP/17 Climate Conference last week during the European summit yet drawing far less attention from the mainstream press. The shrinking biocapacity of our planet (its ability to provide a growing and more prosperous population, cheap energy, fresh water, and food, and to absorb our increasing carbon waste) is rushing in on us like a freight train. According to the latest Global Carbon Project report, C02 emissions jumped by a record 5.9% in 2010, after dropping 1.9% in 2009 as a result of the global recession. The absolute increase in 2010 of a half-billion tons of extra carbon dumped into the atmosphere is the largest ever.

Source: Joe Romm, Climate Progress As we watch our European friends struggle to negotiate collaboratively, in fits and starts, toward a new shared prosperity in the midst of crushing economic pressure, and as we watch the United Kingdom disengage over the fear that its “national interests” (ie, its fiscal dependency on the City of London as the speculation capital of Europe) will be challenged, we had better turn our attention to reality. The looming biocapacity deficits, which will not hit countries equally, will impose a whole new meaning on the word austerity. This will dampen economic growth in the aggregate, and will usher in seismic shifts across industries. We should resolve our unsustainable debt burdens sooner rather than later, and use the crisis in Europe to pave the way for a transition to a more sustainable economy. Along the way we may learn vital lessons on the challenges of managing sovereign interests in an interdependent world.