When I worked at JPMorgan in the 80s and 90s, even in the context of deregulation, the concept of “self-regulation” in the financial industry was discussed with a straight face.

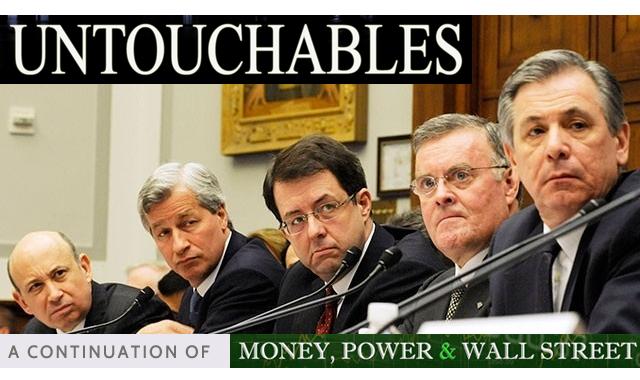

Last week, Better Markets, a sophisticated civil society non-profit organization, run by former Skadden attorney Dennis Kelleher and committed to protecting the public interest in the

government’s regulatory response to the financial crisis, filed a lawsuit against the Justice Department and Attorney General Eric Holder. The suit seeks to block what Better Markets calls an “unlawful” $13 billion settlement with JPMorgan Chase & Co. over bad mortgage loans sold to investors leading up to the crisis. We now have lawyers suing the United States Attorney General on the public’s behalf for failing to properly prosecute a record $13 billion settlement on the nation’s most powerful and flagrant abuser of the self-regulation ethic.How far we’ve come.

Better Markets was appalled that the settlement negotiated in a “secretive backroom deal” gave the bank “blanket civil immunity” for its conduct without sufficient judicial review, according to Reuters.

“The Justice Department cannot act as prosecutor, jury and judge and extract $13 billion in exchange for blanket civil immunity to the largest, richest, most politically connected bank on Wall Street,” Kelleher said.

The consequences of this state of affairs for the real economy and society are enormous. We have a financial sector – the mainstream financial sector, not just the “Long Island bucket shops” portrayed in “The Wolf of Wall Street” – that has decided to abandon a culture of self-regulation even after the financial crisis, which should have humbled and humiliated its leaders. Rather, it is clear that modern Wall Street leadership intends to fight and continue to game the system to their perceived short-term advantage. Which of course is…well, short-sighted. Escalating regulation enforced via lawsuits is a losing proposition for both society and the banks.

How else but this short-sighted, antagonistic approach can one explain the “London Whale” proprietary trading fiasco post the passage of Dodd-Frank legislation that made proprietary trading illegal, the Goldman Sachs alleged illegal agreement to inflate the price of aluminum (which they deny), the Libor scandal, the ongoing FX-rate-rigging scandal, or the British banks avoiding bonus caps via handing out “allowances,” just to name a few top-of-mind examples. Or, how else can one explain the financial industry lobbyist assault on the legislative process following the financial crisis.

As a result, we have legislation ill suited to the task at hand, and creating numerous unintended consequences. As a result, we see a Justice Department–stepping into the breach created by ineffective legislation– seeking to “teach Wall Street a lesson,” creating sympathy on Wall Street for those committing the offenses, while experts looking out for the public interest cry foul about “secretive back room deals” that have enabled the consequences of these offenses to fall only on shareholders and taxpayers rather than on those responsible for the destructive behavior that triggered the economic collapse and left us in far worse shape to manage the next one. Or just ask a real economy bank trying to make loans to the small businesses we need to create jobs about the regulatory effectiveness and its impact on their ability to do their vital jobs. Worse, ask a bank whether the new liquidity rules are consistent with the need for a massive increase in project finance to fund the transition to a clean energy infrastructure?

What to do?

I see only two possibilities, both long shots. The base-case is more of the same. The financial sector continues to exploit and extract, while buying influence in high places to dampen any regulatory or judicial responses. It continues to be hated and mistrusted by society. Its exploitation and extraction continues to widen wealth inequality, deepening the social tension and exacerbating the many social ills that come with extreme and widening inequality. More busts from excess are in store, while the public sector’s ability to respond becomes weaker, both financially and politically. This path leads nowhere good. Principled leadership and financial statesmanship on Wall Street like we had in the days of Dennis Weatherstone at JPMorgan, John Whitehead at Goldman Sachs, or Felix Rohatyn at Lazard is in short supply today. But principled leadership is of course what we most need.

A second long shot hope is that the business sector, the leaders of the real economy finance is intended to serve, will use their power to demand ethical leadership in the banking sector. After all, no one in business was left undamaged by the financial crisis. No one in business benefits from the lost trust in capitalism itself, or from ever widening wealth inequality that restrains consumer purchasing power, and puts a drag on already strained fiscal conditions that harm business. No one in business benefits from boom/bust cycles created by speculative excess on Wall Street.

So where are the voices of business leaders demanding better behavior from Wall Street? I don’t know. I worry they are afraid to speak up. TBTF banks provide the credit lifeline for too many corporations the next time capital markets seize up. They have too much influence on the herding short-term speculator behavior in capital markets that CEO’s ignore at their peril. They are the critical link to financing outlandish takeovers that CEOs dream up, or financial sponsors dream up that might require the services of those same CEOs while offering them outlandish paydays.

When banking is so powerful that the very business the banks are chartered to serve cannot discipline its business unfriendly behavior through market pressure, we are in a serious state of affairs. I can’t think of a better reason for legislators and regulators to dust off the anti-trust laws and force a restructuring of banking into a less concentrated, more diverse, and more resilient system in which no bank is too powerful to criticize, or too intimidating to hold to minimum standards of business community membership.

If only contemporary Wall Street leaders and their boards of directors could see the wisdom in returning to self-regulatory restraint that their predecessors understood so well. Rather than plotting how to game the system, Wall Street banks would do well to look to the leadership quietly asserting itself in the sustainable banking community. The Global Alliance for Banking on Values’ six principles would be a good place to start. Investors too should turn their attention to these sustainable banking models, which have nicely proven themselves to be steady and resilient, even through the extreme market cycles, as nicely documented in “Real Banking for the Real Economy: Comparing Sustainable Bank Performance with the Largest Banks in the World.”