Peter Victor–eminent ecological economist, winner of the Canadian Council for the Arts’ prestigious Molson Award, and author of Managing Without Growth–challenges us to reframe our economic discussions to focus on managing material and energy flows rather than GDP growth.

The World According to Peter Victor

“When you propose the sorts of changes I do you are put on the defensive. You have to defend them against a rosy “business as usual” future that I do not think will be possible. The question is, what are our best options given that we have entered an era of instability and insecurity? I do not think that the frantic pursuit of continued growth is our best bet.”

An economy that is not pursuing growth can still be dynamic. One draw an analogy to a forest that is in some respects in equilibrium–the total biomass is constant but there is still continual change.”

Peter Victor’s Storyline

Peter Victor confesses that his interest in economics, which he discovered at the tender age of 15, was informed from the outset by a habit of mind prone to question the accepted wisdom. Growing up in Kenton, north London, he had a reputation at school for being argumentative. “I would always think of counter examples,” he reports, “So when I was taught economics, which I thoroughly enjoyed… I loved the structure and the logic of it… I was always thinking of what was being missed, what wasn’t being said.”

In the late 60s, when he was searching for a topic for his PhD dissertation at the University of British Columbia, running endless regression analyses on mainframe computers to test often obscure hypotheses was all the rage among university economists. “But I didn’t want to do that,” Peter recalls. “I didn’t have a particular hypothesis–like the differences in interest rate structures–I wanted to test. I wanted to tackle a bigger topic.”

Gideon Rosenbluth and Peter Victor, collaborators on “the economic growth question.”

Of course one of the biggest ignored topics in the world of mainstream economics was the notion of externalities, and Peter immediately seized on it. He had also become instantly alert to the environmental movement blossoming in the mid 1960s. Putting the two together—the concept of externalities and the huge externality of the environment—he had found the subject of his dissertation.

“I wanted to look at ‘how an economy relates to the environment’ and I asked my mentor Gideon Rosenbluth to supervise me,” Peter reports.“I wanted to include the material flows that connect the economy to the environment in an input output model using a materials balance framework and he said go ahead. So I hammered it out in ten months. It was wonderfully exciting.”

The result was an extension of the conventional input output model of the Canadian economy to include, for the first time, the application of the law of conservation of matter to a national economy. This simple but powerful proposition means that all of the materials (including all fossil fuels) required for the economy to function eventually leave as waste, most in less than a single year. Material (and energy) flows can be tracked and related to the behavior of the economy. Peter’s dissertation became the basis of his first book, Pollution: Economy and Environment (1972).

He dedicated another book published the same year, entitled Economics of Pollution, to his grandfather, who had taught him not to drop toffee wrappers on the ground. “I remember walking with him and he would reach into his pocket and offer me a toffee. He would then put his hand out for the wrapper… nothing was said and yet it is an image that has stayed with me forever,” Peter reflects. Indeed, it awakened in him a lifelong sensitivity to, and interest in, the relationship between the economy and the physical world in which it is embedded.

After 3 years as a university lecturer in the UK, Peter served as the Ontario Ministry of the Environment’s first economist. He went on to work as an environmental and energy policy consultant in the private sector, and later as Assistant Deputy Minister of the Environmental Sciences and Standards Division in the Ontario Ministry of the Environment. From 1996 to 2001 he was Dean of the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University in Toronto, and thereafter resumed his academic life as a professor in environmental studies at York.

His return to academia also made it possible for Peter to focus on a topic that had long intrigued him: “the economic growth question.” His formal research began as a collaboration with his former PhD supervisor, and, after publishing a number of papers on the topic with Rosenbluth, Peter wrote the seminal volume: Managing Without Growth: Slower by Design Not Disaster. Although Rosenbluth died in 2011, Peter notes that their genes continue to collaborate, as the marriage of his daughter to Rosenbluth’s grandson has produced two children.

The Five Books That Most Influenced Peter Victor

J.K. Galbraith, The Affluent Society, 1958

W. Leiss, The Limits to Satisfaction, 1976

J.M. Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936

E.J. Mishan, The Costs of Economic Growth, 1967

K. Polanyi, The Great Transformation, 1944

Our Conversation with Peter Victor

What is the likelihood that the transformations of our economy you describe in Managing Without Growth can become a reality in a timeframe that will allow us to avert the worst planetary disasters?

It is getting easier and easier to pull together data that show we are heading in an untenable direction. We now know that climate change is moving faster than experts had thought likely in the past. That is a pretty horrific context to be working in. I am also disturbed by the increasing loss of species. Peak oil already hit the US a while ago. If you look at these phenomena one after another and you understand that economic growth as we have known it means increasing energy and material throughput, it all looks pretty bleak. Being able to show that there is a way forward that can head us in a different direction is important, though it will require substantial changes in many aspects of our economy and our lives in general.

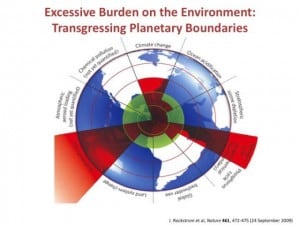

The global economy is placing an excessive burden on the biosphere. Scientists have identified three major issues indicating that the world economy has already exceeded the safe operating space of the planet (indicated in green)—climate change, the nitrogen cycle, and biodiversity loss. Source: Nature, October 2009, Stockholm Resilience Centre.

But asking about the likelihood rather than the feasibility of these changes is somewhat different. I am personally concerned that we have a limited capacity to think long term and globally. As a species we have not been required to do this until recent times. If we can’t do it as individuals, can we at least build institutions that can take the longer and broader view? The trouble is when I look around it is not clear that our institutions have moved in that direction. Our politicians are thinking of the next elections, and our commercial and financial institutions are looking very much to the short-term. Even universities have perhaps lost their way. It is troubling.What I tried to show in the book is the feasibility of a macro picture for a national economy where the economy is not growing much or at all but key social, economic and environmental objectives are being met. My thought was that if this were possible it would open up a discussion about a wider range of options, for rich countries in particular, than the pursuit of economic growth.

Can we thoughtfully steer our way through this? I think we can and that it is possible. But I also think the institutions we have now are not fit for purpose.

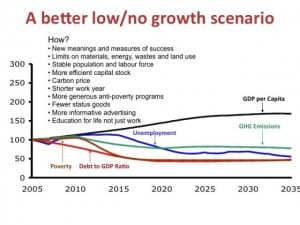

In Managing Without Growth you explore a model that seeks to determine whether it is possible to achieve prosperity–defined as the eradication of poverty, full employment, and substantially reduced greenhouse gas emissions –in a slow or no growth economy. In your more recent work you push the envelope further–raising the possibility of degrowth and prosperity in the developed world.

Yes, in the book I explored alternative scenarios for an advanced economy to simply relying on continual economic growth. I looked at what happens if the growth rate is slowed until the economy is not growing at what is possible under those conditions. When I was writing the book I was not aware of the discussions in Europe about degrowth and had not really thought about the possibilities. The first international conference on degrowth was held in 2008 and I completed Managing Without Growth in 2007. After the book was published I was invited to speak at the second international degrowth conference in Barcelona. I used my original macro model to examine a degrowth scenario for Canada. What would be possible in a smaller economy? I found I could use the model to generate degrowth, defined for this purpose as reduced GDP per capita, and still have full employment, much lower levels of poverty, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and still maintain fiscal balance, but it was not easy.

However, the reaction at the conference intrigued me–few questioned how difficult it would be to achieve the results. It was more, ‘isn’t it good news that it is possible?’ For many degrowth enthusiasts a reduced level of GDP is incidental. There are many in the degrowth movement who are rightly questioning what life is about. They are looking to rebalance work and leisure and build community. I talk about some of these things in my book but they are a more central focus in degrowth discussions. [Note: The first International Conference on Degrowth in the Americas will be held in Montreal in May 2012.]

That takes us to the internal consciousness shifts that have to happen at the individual and societal level to enable the corresponding shift to a no growth or degrowth economy.

Peter Victor’s grandfather, Philip Simons, who taught him not to drop toffee wrappers on the ground and to whom the book Economics of Pollution is dedicated

Many years ago I read William Leiss’ The Limits of Satisfaction where he talks about how advertisers put their products in settings that have nothing to do with the products. For instance, motor vehicles are shown on cliff tops or on beaches where people can’t drive. It’s ironic that advertisers know that people value the natural environment, and use that to sell their products, but I don’t think the rest of us have learned this lesson or fully appreciate what it will take to protect nature from our excesses.These changes will not happen in our society unless people want. It isn’t likely that politicians will lead the change without public support. For example, it will be people saying we do not want to work so much and realizing that North America has fallen behind Europe in this respect. We work many more hours than Europeans over a year, yet a reduction in average hours worked is a way of reconciling a slower rate of growth with an increasing level of employment. We should look at ways to make this possible through changes in policy in the public and private sectors. It is certainly worth talking about. More leisure time with a decent standard of living seems like an attractive scenario to me.

Although you use the term no growth and degrowth you emphasize that policy makers should focus not on containing or managing GDP growth but on managing material and energy flows.

I would emphasize the following: the real area we need degrowth is in material and energy flows and land use. What the economy is capable of doing within those constraints remains uncertain. I think we will find that by the traditional measure, growth can’t continue if total material and energy flows are going down. Policy measures should focus on containing material and energy flows, and land use rather than low or no growth in GDP. But in the absence of good, comprehensive data about the biophysical requirements and impacts of the economy, GDP serves as a proxy, though an imperfect one.

I deliberately called the book “Managing without Growth” instead of “zero growth” because I wanted to shift attention away from growth as a policy goal. I don’t think we should try to adopt zero economic growth as a policy goal. In my experience in various policymaking roles proposals to tackle environmental protection, social justice and so on are tested against their impact on growth rate. Very often this is an inappropriate test. So I am trying to show that if we could manage without growth we don’t have to worry about these growth impacts if we are thoughtful about it. We should think instead about more sensible measures of success in our society and how best to pursue them.

If we were to focus on tangible goals that most can agree on, like increasing life expectancy or literacy or reductions in poverty, then we could strive to achieve them and whatever growth rate falls out would be a matter of second order importance.

It is also important to point out that developed countries have had tremendous economic growth yet the record in terms of other objectives has not been that great. For example, in the past three or four decades poverty has not declined in Canada, incomes and wealth have become more unequal, we have not had full employment, and our greenhouse gas emissions have risen. We need to change the focus of the debate.

You avoid expressing a point of view about whether capitalism is compatible with a world where material inputs into the economy are declining.

This is an important question. I believe the best way to resolve it is to focus in on the changes we have to make to our use of resources, creation and disposal of waste, and land use. We have to be very disciplined about these matters and then we will see if capitalism is compatible with the required changes.

I think 50 or 100 years from now when people look back at what happened, whatever the system is they will be living in it will look very different from what we have today. Whether it is a further evolution of something called capitalism or if the capitalist era will be over I can’t predict. But we are clearly in a process of significant change and I think it will continue.

To what extent is our financial system compatible with an economy that requires degrowth in materials and energy throughput?

While I didn’t really examine the financial implications of our current predicament in Managing without Growththe recent and ongoing financial crisis has led me to think more about them. I believe we went wrong when the financial economy began to run the real economy instead of serving it. What will be required now if we are to set things right is that financial institutions need to be attuned to serving the real economy, by which I mean the production and distribution of goods and services. If that means slower real growth rates, monetary policy should deliver it. I don’t fully understand the obstacles to that happening, but it will take at least a redefinition of the goals of monetary policy and I suspect a redesign of our monetary institutions. The current fragility of the financial system is having repercussions on the real economy, and hence on the natural environment, which will force changes in any event.

You are concerned about the lack of rigor in the prevailing definitions of “green” growth. How can we address the definition with more rigor?

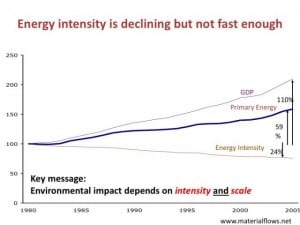

There is much talk about green growth without it being properly defined. Clearly, a reduction in environmental impact per unit of output, which we refer to as intensity, is insufficient if the gain is wiped out by increases in total output.

I became really interested in the interplay between scale and intensity and out of that interest emerged a definition of green growth: increases in scale that are slower than reductions in intensity. Only this combination of changes in scale and intensity guarantees a reduction in environmental impact. Once green growth is defined in this way it becomes apparent that you can have other combinations of scale and intensity. Some people focus on the decline in intensity and call that green growth without looking at the overall impact. But what if intensity declines but not as fast as scale? Then you have an increase in total impact, which is brown growth.

So I think green growth has to mean an absolute reduction in a wide range of environmental impacts while the economy expands, if that is possible.

Although technological advances have enabled a decrease in global energy intensity–as defined as a decrease in energy per unit of output—global primary energy use has risen because increases in absolute output have wiped out decreases in energy intensity. The same is true in the case of materials—total resource extraction continues to increase despite declines in material intensity as the increase in scale of the economy outpaces material intensity declines.

Related to the rigor we need in discussing “green growth,” you emphasize that we cannot expect the fruits of technological innovation to enable continued unfettered growth although some believe technological advances will allow us to continue to decrease resource throughput per unit of production. Can you explain why?

We can certainly use resources in a more efficient way but there are limits imposed, in this case, by the second law of thermodynamics. For example, technologies that increase the rate of reuse or recycling can help increase the size of the economy in the short term but can’t do it in the long term. Eventually we have to go back to nature to take increasing amounts of virgin materials to support continued growth. The record shows that the use of energy and material per unit of output has generally declined in many economies, but the scale of these economies has been rising faster than the rate of that decline. As a result, despite considerable technological advances, the total use of materials and energy continues to rise. The prospects for turning this around do not look promising to me as we move to lower and lower grades of ore and to sources of fossil fuels that are increasingly difficult to access.

If we can get prices to more reasonably reflect the impacts of our economic activities on the environment it will have a beneficial effect on technology. I have not given up on the price system but we have to make it work more to our advantage.We are risking overestimating the contribution from more efficient technologies because we often underestimate their behavioral impacts, which can reduce or negate their otherwise beneficial effects on resource use and waste generation. When a technology increases efficiency it lowers operating costs, as in hybrid cars or compact fluorescent light bulbs, for example. These cost savings may induce people to drive further and more often or to leave the lights on longer. These changes in behavior reduce the savings from the technologies. Furthermore, if the more efficient technologies do bring financial savings, albeit less than expected, they will be spent on other products or services that would not otherwise have been purchased. These rebound effects, first noted in the 1860s by William Stanley Jevons, reduce the gains from more efficient technologies. Only if we have limits on the total material and energy flows that we use to drive the economy can we be sure to benefit from improved technologies without increasing their overall environmental impacts.

Can you talk more about how we can realize a dynamic economy without material and energy growth?

An economy that is not pursuing rapid growth can still be dynamic. It is not just a question of slowing growth rates. We also have to change the composition of what we produce and consume, how they are shared, and how we dispose of waste. There has to be a lot of technological change geared more to increased leisure time and protecting the environment than increasing output. It could open up some very attractive investment opportunities for companies committed to this direction of change but it would be hard on those that resist it.

I sometimes like to draw an analogy to a forest that is in some respects in equilibrium—the total biomass is constant but there is still continual change. Some trees are growing and others are dying but the total stock doesn’t keep rising so the requirements that are put on the rest of biosphere are also in balance. The trouble is that our current system of economics is based not on biological principles but more on physics. We can learn a lot from the natural world when trying to understand the economy.

You make the point that if we prepare for slower growth we stand a reasonable chance of experiencing less disruption and more security than if we don’t.

When you propose the sort of changes I do you are put on the defensive. You have to defend them against a rosy “business as usual” future that I do not think will be possible. It’s an unfair and misleading comparison.

For me the starting point is how things will unfold if we don’t consciously and thoughtfully try to prepare for a future that will be very different from the past. Proceeding blindly, we will see a period of great uncertainty and instability, wild fluctuations and environmental decline. That to me is the proper point of comparison. The question is, what are our best options given that we have entered an era of instability and insecurity? I do not think that the frantic pursuit of continued economic growth is our best bet.

Peter Victor’s model suggest that when low/no GDP growth is deliberately engineered through enlightened public and institutional policymaking and is supported by shifts in individual and community attitudes toward consumption and well-being–see the HOW? above–it can result in declines in GHG emissions, unemployment, poverty, and the debt to GDP ratio. Chart above from P. Victor, Managing without Growth, Edward Elgar, 2008

You say policies have to change on many fronts.

We will need changes in government policy but also private companies have policies that will have to change, as will institutions like universities. All will be affected by a societal shift toward low or no growth. The key government policy changes will need to be ones that put limits on throughput, limits on land and water use so we protect biodiversity, and giving people more choice over time spent at work with a view to reducing work time. Policies for increasing social justice are really important. I expect we will have to change the traditional bases for entitlements in the economy to ones less dependent on paid employment and private profits.

All this will require changes in the stories we tell ourselves as individuals and as members of much larger communities, some of which have already started at the grassroots level, though not much in policy circles.

Are you beginning to see a community building around “managing without growth?”

There is a level of interest in these ideas that I would never have anticipated, and it is happening internationally. However, it is an open question, whether this change in what people want out of life and as individuals and communities is a passing phase or a movement that is building. I don’t know how it is going to turn out. We need pressure from below and leadership from above. The pressure is building but where are the leaders? When will they get the message?

Find out more about Peter Victor and his work at his website.

—Susan Arterian Chang is Director of Capital Institute’s Field Guide to Investing in a Regenerative Economy project.

UPDATE: Peter Victor’s Presentation at the Institute for New Economic Thinking Paradigm LostConference